80. Anne Ryan

| Life Dates | 1889-1954 |

| Place of Birth | Hoboken, NJ, USA |

| Place of Death | Morristown, NJ, USA |

| Birth Name | Anna Ryan |

Born “Anna” in 1889 in New Jersey to an Irish-Catholic family, Ryan was from the age of fourteen raised by her grandmother after her father died in 1902 and her mother committed suicide in 1903.1 She attended a Catholic preparatory school, the Academy of Saint Elizabeth in Covenant Station, New Jersey, and matriculated to the affiliated College of Saint Elizabeth, where she developed a love of poetry and art. In April 1911 during her junior year, she married William McFadden, a lawyer two years her senior who lived across the street from Ryan’s family’s beach house in Asbury Park. Ryan left college before graduating, and the couple quickly welcomed twins, Elizabeth and William Jr., in April 1912 and a third child, Thomas, in 1919. The marriage deteriorated shortly thereafter because of William’s mental health—he suffered from delusions and paranoia and was eventually institutionalized at a state-run mental institution—and the couple separated in 1923.2

With William no longer able to support the family, Ryan suddenly was on her own financially. Money was extremely tight in the ‘20s as she looked for opportunities to earn a living. She gravitated towards writing fiction and poetry, which had been her focus in college, and soon published a collection of poems titled Lost Hills (1925). A book manuscript, One Life, Raquel, and several other short stories and poems went unpublished but are preserved in the manuscripts collection of the Newark Public Library. Demonstrating an early proclivity for networking and self-promotion, she began exploring the avant-garde literary scene in New York City’s Greenwich Village (though she continued to live in New Jersey). Eventually, she found her way to Daca’s bookshop, which was located on Washington Square, and befriended a circle of bohemian writers, actors, and artists.3

In another somewhat bold decision, Ryan departed in 1931 for Mallorca where she had heard from friends that living was cheap. While abroad, Ryan wrote a biography of the eighteenth-century Franciscan missionary Junípero Serra and a number of articles called “Spanish Sketches,” some of which appeared in newspapers back home like the New York Sun.4 When she returned to America two years later, Ryan continued to write professionally and also established a bakery in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, struggling to make ends meet. Apparently, Ryan had trouble qualifying for government relief programs of the New Deal through she desperately needed the support; despite the fact her husband was institutionalized, her status as married seems to have complicated the screening process.5

Around the time her older children graduated college in 1934, her daughter’s then-boyfriend Tony Smith (1912-1980), who would become a noted minimalist sculptor, urged Ryan to abandon the bakery and move to Greenwich Village.6 This was the germinal moment of Ryan’s life—in her mid-40s—when she transitioned from writing and “became” an visual artist. Living in the Village, initially at 104 West Fourth Street, exposed her to the avant-garde community of artists in a more immersive way than her initial forays into the city’s literary world during the 1920s. “This is my district,” Ryan often proclaimed emphatically about living in the Village, which to her daughter suggested the new environment “so galvanized her that it filled her with a feeling of omnipotence.”07 As recorded in her diary, she began painting in 1938—first in pastels, later oil—and they tended to focus on cityscapes, still lives, and portraits of family and friends. Eventually, she began painting abstractly, as seen in an untitled canvas that was once in the collection of critic Clement Greenberg (now in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum). In April of that year, Ryan’s second-floor neighbor Giorgio Cavallon (1904-1989), a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, brought Hans Hofmann by to see her work.8 The esteemed teacher liked her work, particularly her portraits, and recommended she continue painting without taking a formal art education. She took this comment to heart, later noting in her diary, “The self-taught are more apt to create spontaneously than those academy taught.”9

At this point, her artistic career began to accelerate fairly rapidly. In the winter of 1941, she and her younger son moved to a larger ground-floor apartment on Greenwich Street, which gave her more space to work. In March, she exhibited paintings—mostly all abstractions—at The Pinacotheca on Madison Avenue and received mostly favorable reviews.10 Later that year, she visited the New School for the first time with a friend where she encountered Stanley William Hayter and the artist Ralph Rosenborg (1913-1992), who she noted were both “excellent painters,” and she immediately wrote to Hayter about the possibility of a scholarship to take his class.11 Never having experienced formal artistic training, the Atelier 17 classroom was exhilarating for Ryan. She took copious notes of Hayter’s lessons—from specific technical instructions and marketing one’s career to overarching ideologies about automatism—and enjoyed the extraordinary benefits of this close community of artist-printmakers.

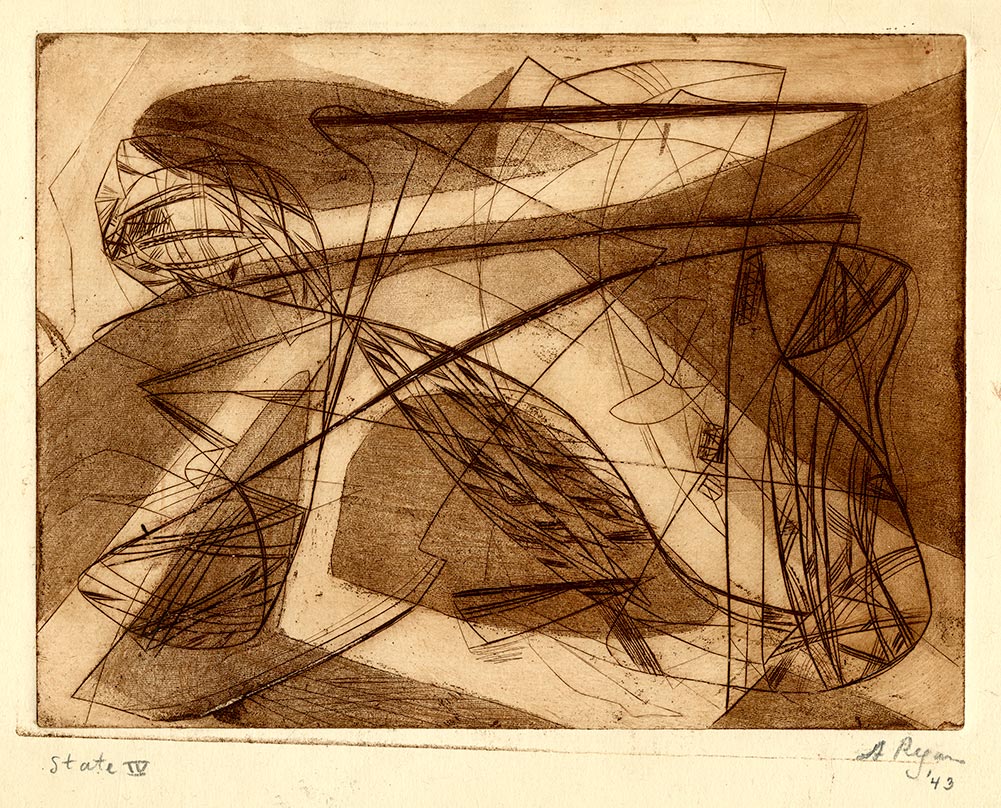

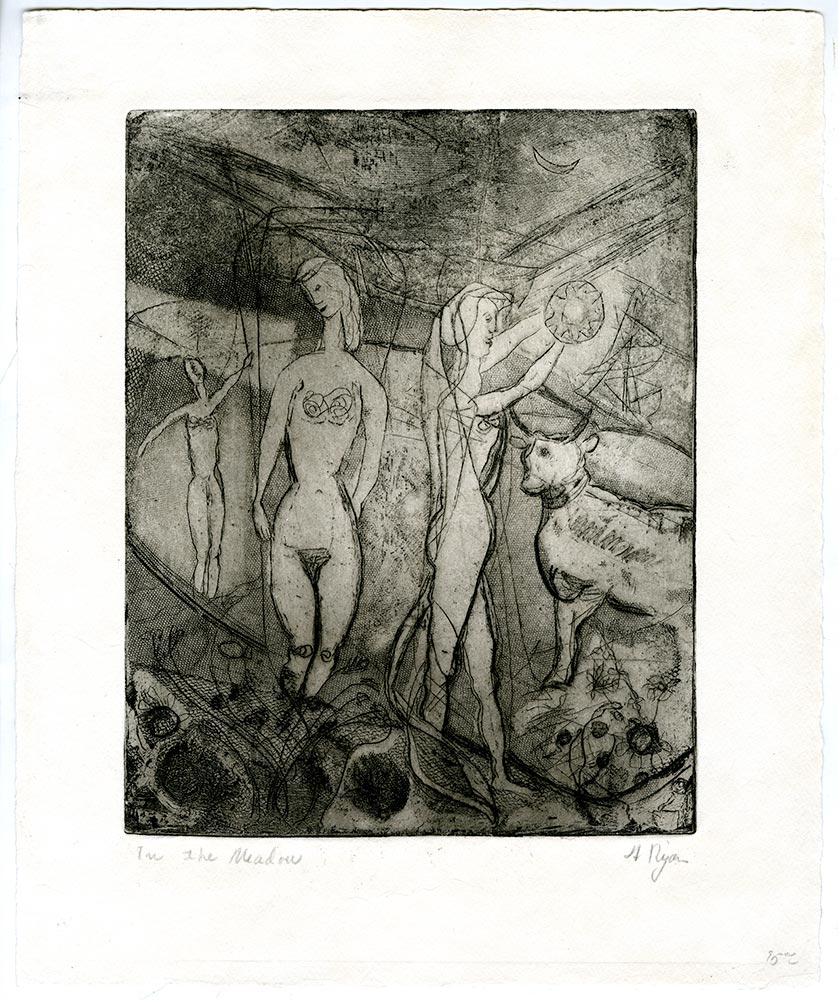

Her printmaking output is divided into two distinct parts: etchings she made between 1942 and approximately 1945; and colorful woodblock prints, mostly printed on black paper, between roughly 1945 and 1949.0 The subject matter she covered in these etchings and woodcuts was extremely varied and included religious imagery, still lives, circus performers, portraits, abstractions, and surrealistic situations with female dancers and isolated women. Ryan worked tirelessly to get these prints shown in commercial galleries and other cultural institutions, both in the United States and abroad. The successes she had as a printmaker gave her confidence, with her non-traditional background, to continue pursuing a professional artistic career. Ryan died suddenly of a stroke in 1954, and her daughter Elizabeth McFadden dispersed large gifts of her prints and collages to several institutions, such as the Metropolitan Museum, Museum of Modern Art, and the Brooklyn Museum.

Archives

Anne Ryan Papers, 1922–1968, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Anne Ryan Papers, Scripts and manuscripts, Newark Public Library, Art and Music Division, Newark, NJ.

Selected Bibliography

Anne Ryan. New York: Kraushaar Galleries, 1957.

Anne Ryan: A Retrospective, 1939-1953. New York: Susan Teller Gallery, 2007.

Anne Ryan: Collages. New York: Marlborough Gallery, 1974.

Armand, Claudine. Anne Ryan: Collages. Giverny, France: Musée d’Art Américain, 2001.

Cotter, Holland. Anne Ryan: Collages from Three Museums. New York: Washburn Gallery, 1991.

———. “Material Witness.” Art in America 77 (November 1989): 176–83; 215.

Faunce, Sarah. Anne Ryan Collages. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum, 1974.

Haxall, Daniel Louis. “Cut and Paste Abstraction: Politics, Form, and Identity in Abstract Expressionist Collage.” PhD diss., The Pennsylvania State University, 2009.

Myers, John Bernard. “Anne Ryan’s Interior Castle.” Archives of American Art Journal 15, no. 3 (1975): 8–11.

Rooney, Judith McCandless. Anne Ryan Collages & Prints. Houston, TX: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1980.

Solomon, Deborah. “The Hidden Legacy of Anne Ryan.” The New Criterion, January 1989, 53–58.

Windham, Donald. “Balance, Elegance, Control: Anne Ryan and Her Collages.” Art News 73, no. 5 (May 1974): 76–78.

Notes

- Elizabeth McFadden to Robert Koenig, February 10, 1979, 1, Anne Ryan Papers, Art and Music Department, Newark Public Library; Claudine Armand, Anne Ryan: Collages (Giverny, France: Musée d’Art Américain, 2001), 70. ↩

- Anne Ryan and William McFadden never divorced, and it is not known whether their union remained for religious reasons or legal practicalities (i.e., that one of the parties was mentally ill). In any event, Ryan checked with the state-run institution about McFadden’s condition at least four times in 1939, 1942, 1946, and 1948). See letters on reel 86 of the Anne Ryan papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (henceforth ARP). ↩

- Elizabeth McFadden, “Anne Ryan,” The Saint Elizabeth Alumna, Spring 1956, 5. ↩

- Anne Ryan, “After Church in the Perfumeria,” New York Sun, April 4, 1933, ARP, reel 88:876. ↩

- McFadden to Koenig, 2. All artists seeking a relief position within the WPA-FAP had to substantiate their artistic qualifications, which could consist of press clippings, portfolios of work, and exhibition brochures. Outside of their qualifications for the FAP, women generally had trouble meeting eligibility guidelines for WPA relief. For any person, regardless of gender, qualifying was a maddening process of proving financial need and divesting oneself of everyday comforts. Women faced additional obstacles since the WPA would only approve a female applicant if she were deemed the head of household; if married, her husband had first priority for relief work. See Chapter 1 of Kimn Carlton-Smith, “A New Deal for Women: Women Artists and the Federal Art Project, 1935-1939” (PhD diss., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1990). ↩

- McFadden to Koenig, 1. ↩

- She had help with the restaurant venture from her sons, Tom (who was living with her) and the older Liam. McFadden to Koenig, 2. ↩

- It is sometimes reported that Fritz Bultman (1919-1985), a painter who lived down the street, brought his friend and teacher Hans Hofmann to see Ryan’s work. But, Ryan’s diary clearly says it was Cavallon. Anne Ryan, diary, 1938, 1941-2, ARP, reel 87:389. ↩

- Anne Ryan, diary entry, February 7, 1942, ARP, reel 87:430. ↩

- Anne Ryan: First One Man Show (New York: The Pinacotheca, 1941), APR, reel 88. For reviews of this show, see unknown review, ARP, reel 88:894; “The Passing Show: Anne Ryan,” Art News 40 (March 1, 1941): 46; 52; “Anne Ryan at Pinacotheca,” Art Digest 15, no. 12 (March 15, 1941): 9. ↩

- Anne Ryan, diary entry, October 23, 1941, ARP, reel 87:404. ↩