13. Louise Bourgeois

| Life Dates | 1911-2010 |

| Place of Birth | Paris, France |

| Place of Death | New York, NY, USA |

| Birth Name | Louise Bourgeois |

Born in 1911 in Paris, Bourgeois grew up in a fairly well to do family who operated a tapestry restoration business. Her life was fairly uneventful until Bourgeois’s father began an affair with his children’s English tutor, and the trauma of his infidelities and her role as a go-between for her parents would remain with the artist for her entire lifetime.1 After high school, she briefly pursued a degree in mathematics at the Sorbonne (partially to escape her father’s influence and the grief of her mother’s death), but quickly gave it up in favor of artistic studies. During the mid-1930s, Bourgeois attended a number of art schools in France—including the École des Beaux Arts, Académie de la Grande-Chaumière, Académie Ranson, Académie Colarossi, and Académie Julian—in a frenetic burst of independence and creative exploration.2 The unconventionality of these various institutions and her instructors was immensely energizing to the young Bourgeois who had, to that point, lived a very conventional existence. In addition to meeting fellow bohemians in school and learning modernist ideologies, she also brushed shoulders with Paris’s surrealist community, having rented an apartment above André Breton’s Galerie Gradiva (but she never formally introduced herself to any of these figures).3 In August 1938, her world changed forever when a young American art historian, Robert Goldwater (1907-1973) walked into the small gallery she operated out of her family’s tapestry gallery. The two wedded only three weeks later and departed a month after that for New York City.

Adjusting to her new life in the United States was difficult. With her husband occupied by teaching and writing, Bourgeois was free most of the day to wander New York City in what she called a “manageable loneliness.”4 Almost immediately, she sought out the familiar by enrolling at the Art Students League.5 In November through the following May, she was a student in the life class of Vaclav Vytlacil (1892-1984), an American born to Czech parents who trained in Europe with Hans Hofmann and was a founding member of the American Abstract Artists. In the spring, she added etching classes with Harry Sternberg (1904-2001), a noted printmaker and political activist. But this freedom would soon end since Bourgeois and Goldwater welcomed three sons within four years of marrying, one adopted (born 1936) and two biological (born 1940 and 1941). During the most demanding years of her sons’ early childhood, Bourgeois’s diaries are filled with notes about the boys’ health (fevers, cold symptoms, temperaments) and her frustration at not having enough time to work or not accomplishing enough during the time she had available.6 Many of Bourgeois’s prints and drawings from the late 1930s and early 1940s successfully combine these two dominant spheres of influence in portraits of her husband and children in scenes of her domestic activities.

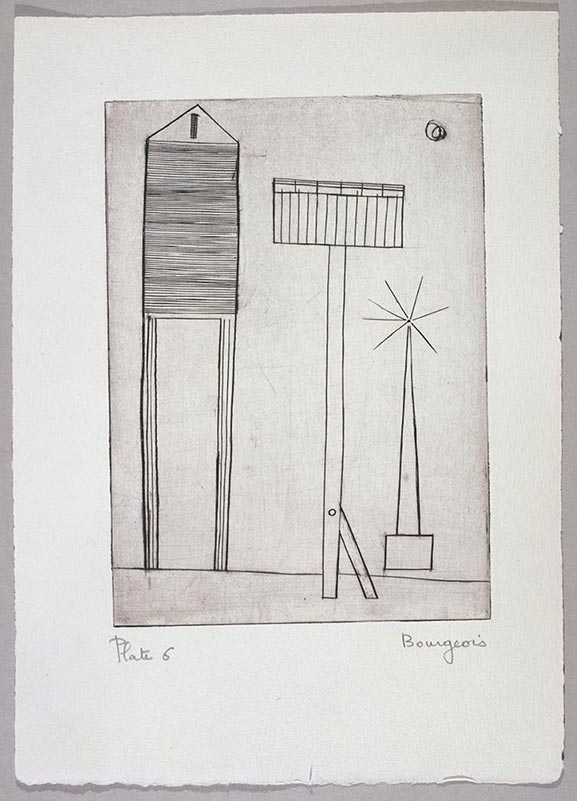

According to her datebooks, Bourgeois began her work at Atelier 17 in the fall of 1946 and continued going there sporadically throughout 1947. During this time, she completed the plates for her illustrated portfolio He Disappeared into Complete Silence (1947), printing the images herself at Atelier 17. Gemor Press printed the accompanying text and distributed the book.7 The postwar period’s burgeoning print market must have incentivized Bourgeois to produce He Disappeared into Complete Silence. As she later told several interviewers, this portfolio and her other single prints were a way to gain exposure within the New York art world and build a professional reputation.8 In 1945, she had had her first solo show of paintings at Bertha Schaefer Gallery, but was still looking for ways to increase her visibility. Although she and Goldwater operated in the highest echelons of New York City’s cultural circles, joining Atelier 17 was a way for Bourgeois to feel personally connected to New York’s tight-knit printmaking community (an added bonus was the workshop’s many French speakers). She made many friends as a result of her Atelier 17 affiliation, including the Brooklyn Museum’s print curator Una Johnson, the architect Le Corbusier, Spanish surrealist Joan Miró, and Chilean artist Nemesio Antúnez.9 Through the process of making the He Disappeared into Complete Silence portfolio, Bourgeois also became invested in architectonic constructions and translated them to freestanding sculptures, which were shown in succession at Peridot Gallery between 1949 and 1953.

Archives

The Easton Foundation, New York, NY.

Selected Bibliography

Bewley, Marius. “An Introduction to Louise Bourgeois.” The Tiger’s Eye 7 (March 1949): 89–92.

Cluitmans, Laurie, and Arnisa Zeqo, eds. He Disappeared into Complete Silence: Rereading a Single Artwork by Louise Bourgeois. Haarlem, The Netherlands: De Hallen Haarlem and Onomatopee, 2011.

Katz, Vincent. “Louise Bourgeois: An Interview.” The Print Collector’s Newsletter XXVI, no. 3 (August 1995): 86–90.

“Louise Bourgeois.” Magazine of Art 41 (September 1948): 307.

Morris, Frances, ed. Louise Bourgeois. New York: Rizzoli, 2008.

Storr, Robert. Intimate Geometries: The Art and Life of Louise Bourgeois. New York: The Monacelli Press, 2016.

Wye, Deborah. Louise Bourgeois. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1982.

———. Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait: Prints, Books, and the Creative Process. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2017.

Wye, Deborah, and Carol Smith. The Prints of Louise Bourgeois. New York: Museum of Modern Art; distributed by H. N. Abrams, 1994.

Notes

- For a comprehensive record of Bourgeois’s childhood, see chapter 1 of Robert Storr, Intimate Geometries: The Art and Life of Louise Bourgeois (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2016). ↩

- Robert Storr’s extensively researched monograph covers the period of Bourgeois’s academic training in great depth. See Intimate Geometries, 64–73. ↩

- Mignon Nixon, Fantastic Reality: Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art (Boston: MIT Press, 2005), 15; Storr, Intimate Geometries, 74. ↩

- As quoted in Storr, Intimate Geometries, 78. ↩

- Student registration card, Art Students League of New York. ↩

- Thank you to the Easton Foundation for making these diaries available to me. Bourgeois was privileged to have domestic help, and she generally had the mornings free to work. Storr, Intimate Geometries, 80–81. ↩

- Deborah Wye and Carol Smith, The Prints of Louise Bourgeois (New York: Museum of Modern Art; distributed by H.N. Abrams, 1994), 72–73. ↩

- Vincent Katz, “Louise Bourgeois: An Interview,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter XXVI, no. 3 (August 1995): 88; Storr, Intimate Geometries, 95. ↩

- Storr, Intimate Geometries, 122–23. ↩